We shouldn't be to surprised to discover that

oil companies pay millions to lease tracts of the gulf. Mother Jones attempts some indignation – "Where most people look at the Gulf, they see a vast marine ecosystem, wetlands, and, until recently, gorgeous beaches" – I find it difficult to be surprised when we've treated all our land-based natural resources this way for the entirety of our country's history. My question, which I couldn't seem to find addressed in the Mother Jones article, is: who is the recipient of the payments in these leases, as high as 53 million dollars? From whom do they lease?

Robert Reich continues to defend the idea that Obama should

take over BP's American operation, specifically responding to the charge that, since the problem is not something that can be solved right away, it would be a political folly to take ownership of the mess when the conclusion is so far away. And true, it is a worrisome prospect to put the government in charge when many Americans are distrustful of government takeovers. My personal take at the moment would be closer to

Reich's, that BP is still responding in the way that maximizes shareholder value. The government is answerable to its citizens – at least in theory – BP holds no such pretense.

Reich also suggests that BP should be

required to hire unemployed youth to clean up the spill. BP, instead, is spending money trying to pick up some of your

search results, undoubtedly so they can show you

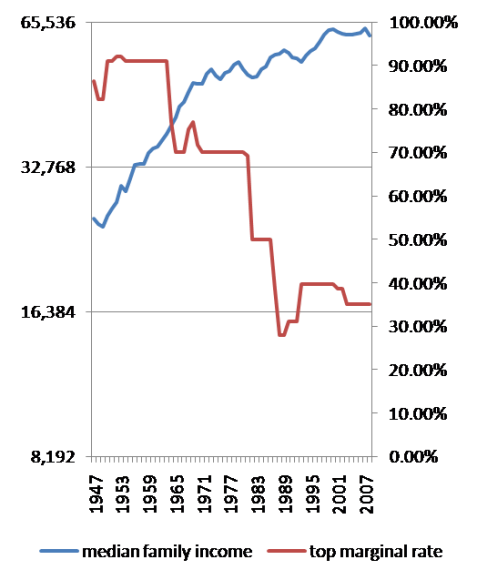

misleading charts.

If there isn't enough incentive already to tax carbon (or otherwise shift energy sources), evidence has been found that the presence of the industry

enforces patriarchy:

Oil production reduces the number of women in the labor force, which in turn reduces their political influence. As a result, oil-producing states are left with atypically strong patriarchal norms, laws, and political institutions.

Speaking of gender norms, comedic genius Sarah Palin suggests in a post titled "Less Talkin', More Kickin'" that Obama should solve the oil leak by

talking to a few more people, including all of Tony Hayward, "experts," and, um, her.