I tend to think of religions across three categories of things they provide: metaphysics, imperative, and community. "Metaphysics" in this context refers to what one believes is true about the world: Does god exist? Is there afterlife? Can we freely make choices in our lives? "Imperative" refers to what one should do about it. Should I help the poor? Should I hate gays? Is my salvation dependent upon my holding a concise set of metaphysical beliefs? "Community" is unique in this context, as it stems from the religion's imperative, i.e., a religion will tend to state that you should gather around those with similar beliefs. However, it seems to be to deserve separate mention in that: (a) For a given individual's decision making process, a selection of a religion most often comes with an existing community, and (b) it is one thing, like the other two, for which an individual will typically need to find a source if choosing to abandon a religion, or religion in general.

When the Dawkinses and Hitchenses of the world begin their arguments to undermine religion, they usually focus on this first category. "There is no evidence" is likely the most oft repeated expression, focusing on matters such as god's existence, earth's age, and natural selection. One problem with this line of argument is that it presumes a logical framework in which a person should not believe any thought for which there is no evidence, as opposed to, say, a framework in which people believe whatever thoughts occur to them until there is evidence to the contrary. This latter logical framework would still force a person to reconsider a belief in a young earth, but something like god's existence might have an easier time surviving. My question, however, is: what should inform our metaphysics, i.e., what should constitute evidence? Though the religious will not use the word "evidence" to describe their reasons for believing in, say, god's existence, the things they treat as evidence, as things that inform their beliefs, may include holy books, divine revelation, or merely the fact that people have believed this for centuries as part of a cultural tradition. It is my suspicion that this latter category may be the most powerful. Nonetheless, when a religious person hears "there is no evidence," in response to a belief of theirs, their response, though they have not the words to describe it, is that "there is evidence, my evidence is that this has been a long standing belief in my culture and my culture has survived." Perhaps there is reason to admit this as evidence, but only weak evidence if that: it is certainly possible that communities of people survive despite their beliefs.

I have let myself cross over into the "imperative" category (though perhaps sticking closely to that which is closely related to metaphysics), and probably did as soon as I used the word "should." I of course do believe these categories to be closely related, as they do tend to come packaged together. In fact, nearly every metaphysical belief includes the imperative that "I should believe this" though many have no imperative beyond that, i.e., belief in a young earth does not necessarily imply that one should love their neighbour. Even still, the possibility exists that metaphysics and imperative may contradict, i.e., "I believe that X is true, but I believe that I SHOULD believe Y, which contradicts X." This situation would be rare in reality, but theoretically possible. Most formal religions discourage or disallow such a contradiction. But, more on this later, as I believe I've taken a slight bit of a theoretical digression.

Those items in the imperative category are those in which outspoken atheists have a tougher time gaining their footing. Those on the religious side of the argument tend to respond with, "Well, your science may be able to tell you that natural selection is real, but surely it's useless when telling me how to live my life!" This is true of the strictly deterministic sciences, but the probabilistic sciences have more to say in this subject matter. For example, consider the following three arguments:

"We should be radically charitable because the bible or god tells us to"

"We should be radically charitable because my culture has believed this, and our culture has survived."

"We should be radically charitable because anthropological studies across cultures have indicated that those cultures that have a strong altruistic imperative fare best in the long run."

The first is command by fiat. The middle is anecdotal regarding a single culture. The last bears closest resemblance to controlled scientific study. Can I say that that is always best? Perhaps not, but I can say that the latter sort of argument will have the greatest truth in the widest array of contexts compared to the others. Now, I do not wish to assert that for all things deterministic science has an answer. Science admittedly can only inform us fully on those subjects which are deterministic, such as physics and chemistry, or those which can be closely related to a deterministic template using probability, such as psychology and sociology. Effectively, science can not tell us what values to adopt, merely what happens when you adopt those values.

In the context of these recent three arguments regarding radical charity, there is the implied value that "humanity's long-term well-being is more important than an individual's short-term well-being." Moreso, there is the implied value that "it is good for humanity to survive," which is not necessarily true, in fact, science and history have taught us a great deal about what happens to the planet when humanity flourishes. If we were to reconcile a value of humanity's good with the value of nature's good, we might be on the losing end of that battle. If justice were an ideal to be valued, humanity may be on the losing end of that reconciliation as well.

There can be no rational way to reconcile values without arbitrarily drawing upon other assumed values. I thus propose two values I retain based on either faith or delusion (on which any system of values must rely):

I value that which is true in the widest context.

I value humanity's survival and happiness in the long-term.

I attempt to justify these values and I cannot without referring back to them. But I do discover that when I reason from these values, taking the widest array of evidence into account, the evidence proposed by my religious life (as it once was) becomes superfluous. Before deeming it superfluous, I had even become quite adept at using what would be considered religiously-admissible-evidence to reconcile religious truth with what I found to be true in a wider context. But even this turned out to be not only superfluous, but near arbitrary -- usually in the form of picking a verse from the bible to trump some other verse from the bible. But even here, my reasoning resorts to the above-stated value of truth in the widest context.

Though I find both of these values necessary for building any working world view in which to move forward with my life, I find that it will occasionally result in the metaphysics/imperative contradiction aforementioned. For example: I recognize the futility of humanity, but I believe that it is in humanity's best interest to ignore it. Thus haphazardly I've brought myself to the final category in religions, the built-in community. I have often thought, even when I've been more inclined to sympathize with religious beliefs, that I'm a stranger in communities of those with a religious background and those without. Perhaps because I distrust a religion's lack of recognition of humanity's futility, and perhaps I'm bored with the general past times of those who internalize that futility. Perhaps then, this is another intrinsic contradiction of this value system: recognition of the value of (a) community, yet forfeiting your participation in it. In any case, this is category that an individual plays the closest role in creating, and thus it is the category through which I have the hardest time reasoning, and about which I have the least answers.

Is there a thesis, then? Not sure. Perhaps "science can offer us not just metaphysics, but an imperative as well," which would be a message for both the religious and non-religious alike. Perhaps "I have alienated myself from my peers," which is probably a message moreso for me.

Friday, December 25, 2009

Monday, December 21, 2009

Cult of GDP

On the Commons:

When the GDP goes up the media cheers. Economists assume that more expenditure means a better life. This does not speak well for the perceptual capacities of that profession.

We spend a great deal of money when we have cancer, or a car wreck, or go through a bitter divorce, or rack up credit card debt. These all make the GDP rise. They mean life is getting better? Sheeesh.

Friday, December 18, 2009

Fiscal Multipliers and Public Transit

- Every billion dollars spent on public transportation produced 16,419 job-months.

- Every billion dollars spent on projects funded under highway infrastructure programs produced 8,781 job-months.

At least our Transportation Secretary takes Amtrak:

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Ray LaHood | ||||

| www.thedailyshow.com | ||||

| ||||

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Krugman Addresses George

"Well, look. Believe it or not, urban economics models actually do suggest that Georgist taxation would be the right approach at least to finance city growth. But I would just say: I don't think you can raise nearly enough money to run a modern welfare state by taxing land. It's just not a big enough thing."

The context was health care. "We're having enough trouble trying to make sure we repeal the Bush tax cuts," Krugman added, "and trying to shift to a completely different base of taxation is just not going to be on the table."

True, but let's stay in the realm of theory for a minute. Could a land tax pay for a health care system?

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Perhaps there is to much commentary on a single economist here.

Should Americans embrace a more robust social safety net at the cost of much higher marginal tax rates, reduced work incentives, and a smaller economic pie? From a strictly economic perspective, there is no right answer to this question.

...

Put simply, the healthcare reform bill would make the United States more like western Europe. That may mean more security about healthcare, but it also means that future generations of Americans will likely spend more time enjoying leisure.

I love the way that this is expressed. I thought at first that he may have meant that final clause sarcastically, referring to potentially increased unemployment, but his link is not about that potential effect.

For the most part, if the nation as a whole works fewer hours, that is indicative of some percentage of the population losing their jobs, and some working fewer hours than they'd like to to maintain a standard of living. However, if we found that a system could be devised in which the fewer hours could be distributed more evenly – if, for example, everyone worked just a little bit less – we would be more likely to describe it as more time enjoying leisure, instead of "underemployment."

This system would also be predicated upon our ability to maintain a standard of living with fewer national work hours. I'd think advances in technology alone would be enough to accommodate the loss, but again, we currently have a system in which labor-saving technology does not benefit the laboring workforce.

In other news, happy thanksgiving:

You can also read about economic systems that the pilgrims tried.

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Don't we all?

Obama wants worldwide end of fossil fuel subsidies:

Many countries, including the United States, provide tax breaks and direct payments to help produce and use oil, coal, natural gas and other fuels that spew carbon dioxide, the chief greenhouse gas. Eliminating those would provide "a significant down payment" toward the U.S. goal of cutting fossil fuel emissions in half by 2050, Froman said.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Ensign

John Ensign brought public transit into the health care debate.

It reminds me of this Andy Singer comic illustrating all the hidden costs of our automobile culture. I doubt John Ensign is going to use this as a reason to fund public transit or start measures to curb gun deaths.

Republican John Ensign said the numbers were skewed. He pointed out that if automobile and gun deaths were eliminated from the data, the U.S. would rank much higher. Calling these “cultural differences,” Ensign said “in this country, we like our guns” and “we are a more mobile society” who drives more and uses public transportation less than Europe.

It reminds me of this Andy Singer comic illustrating all the hidden costs of our automobile culture. I doubt John Ensign is going to use this as a reason to fund public transit or start measures to curb gun deaths.

Tevye & Perchik

Monday, September 14, 2009

Joe Wilson's Embarrassment

Craig Ferguson and Keith Olbermann have both issued responses to Joe Wilson's outburst from Obama's health care speech, indicating his behavior was an embarrassment to the legislative process and the nation.

Really, I disagree. I think our houses of congress could stand to use a little bit of a relaxing of the rules of decorum. Joe's outburst wasn't quite as bad as South Korea's fistfighting, and really, was rather on par with the standard booing and cheering that would tend to occur during any speech. I might argue our legislators aren't interrupted enough. When a congressman stands in front of his (usually empty) house and the c-span camera and chooses to provide misleading information, there's no reason that person shouldn't be interrupted with exclamations to contrary or at least boos.

Really, I disagree. I think our houses of congress could stand to use a little bit of a relaxing of the rules of decorum. Joe's outburst wasn't quite as bad as South Korea's fistfighting, and really, was rather on par with the standard booing and cheering that would tend to occur during any speech. I might argue our legislators aren't interrupted enough. When a congressman stands in front of his (usually empty) house and the c-span camera and chooses to provide misleading information, there's no reason that person shouldn't be interrupted with exclamations to contrary or at least boos.

Joe Wilson did not embarrass the U.S.; he embarrassed himself.

There were some elements of the speech that might require some skepticism, the least of which was probably the claim to which Wilson objected. The thing I might have been most likely to question was the following: "I will not sign a plan that adds one dime to our deficits -- either now or in the future."

The president has often indicated that he intends the purpose of reform to be to "bend the cost curve," meaning to reduce, over time, the percent of GDP spent on health care. This does not necessarily mean, as is often mistaken, that we will be reducing what share of the health care cost is taken by the state. And though in the end, the cost of reform should be paid for, the time to promise no additional deficit on the state balance sheet is not in the middle of a deep recession.

Really, I disagree. I think our houses of congress could stand to use a little bit of a relaxing of the rules of decorum. Joe's outburst wasn't quite as bad as South Korea's fistfighting, and really, was rather on par with the standard booing and cheering that would tend to occur during any speech. I might argue our legislators aren't interrupted enough. When a congressman stands in front of his (usually empty) house and the c-span camera and chooses to provide misleading information, there's no reason that person shouldn't be interrupted with exclamations to contrary or at least boos.

Really, I disagree. I think our houses of congress could stand to use a little bit of a relaxing of the rules of decorum. Joe's outburst wasn't quite as bad as South Korea's fistfighting, and really, was rather on par with the standard booing and cheering that would tend to occur during any speech. I might argue our legislators aren't interrupted enough. When a congressman stands in front of his (usually empty) house and the c-span camera and chooses to provide misleading information, there's no reason that person shouldn't be interrupted with exclamations to contrary or at least boos.Joe Wilson did not embarrass the U.S.; he embarrassed himself.

There were some elements of the speech that might require some skepticism, the least of which was probably the claim to which Wilson objected. The thing I might have been most likely to question was the following: "I will not sign a plan that adds one dime to our deficits -- either now or in the future."

The president has often indicated that he intends the purpose of reform to be to "bend the cost curve," meaning to reduce, over time, the percent of GDP spent on health care. This does not necessarily mean, as is often mistaken, that we will be reducing what share of the health care cost is taken by the state. And though in the end, the cost of reform should be paid for, the time to promise no additional deficit on the state balance sheet is not in the middle of a deep recession.

Monday, August 17, 2009

Monday, July 27, 2009

Small and Inconsequential

I was reading briefly on the subject of Idaho bike laws, under which cyclists are permitted to treat stop signs like yield signs. This makes intuitive sense given that a cyclist's not-stopping-at-all can often be roughly the same speed as an automobile's rolling-stop.

The following quote stood out:

Why wouldn't cyclists and motorists unite on this subject? Because a cyclist notices energy inefficiency at the moment it occurs: the cyclist has to pedal harder. The motorist doesn't notice the inefficiency until reaching the pump, and at that point it usually gets framed to oneself as a "gas is so expensive!" complaint, rather than a "cities are designed so inefficently!" complaint.

And, even recognizing that the stop-and-go of most day-to-day driving is the cause of much of the inefficiency is another couple of steps away from realizing that the quantity of automobiles contributes to that stop-and-go, and that your-car-in-particular is part of the quantity of automobiles.

The following quote stood out:

The “momentum” argument is garbage. If the stop signs are located for good reasons (not always the case), then conservation of momentum should take a back seat to other considerations. If the stop signs were not located for good reasons, then cyclists and motorists should unite to get them removed.

Why wouldn't cyclists and motorists unite on this subject? Because a cyclist notices energy inefficiency at the moment it occurs: the cyclist has to pedal harder. The motorist doesn't notice the inefficiency until reaching the pump, and at that point it usually gets framed to oneself as a "gas is so expensive!" complaint, rather than a "cities are designed so inefficently!" complaint.

And, even recognizing that the stop-and-go of most day-to-day driving is the cause of much of the inefficiency is another couple of steps away from realizing that the quantity of automobiles contributes to that stop-and-go, and that your-car-in-particular is part of the quantity of automobiles.

Friday, July 24, 2009

Wonkette, Irony & Sincerity

In E Unibus Pluram: Television & US Fiction, David Foster Wallace wrote of irony, "It’s critical and destructive, a ground-clearing... But irony’s singularly unuseful when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks."

In turn, I love reading wonkette, and find it to be kind of like a daily show in print (but with more curse words). I bring this up in this context because in the past two days I found two unexpected moments of sincerity from your wonkette that I found quite pleasing.

The more recent was in response to MSNBC's First Read describing the presidential press conference as too boring and policy-filled:

The earlier was regarding the treatment of congressional interns who answer the phone of constituents across the country, many of whom believe ridiculous things like "the government will invade your house and force you to accept public health care."

In turn, I love reading wonkette, and find it to be kind of like a daily show in print (but with more curse words). I bring this up in this context because in the past two days I found two unexpected moments of sincerity from your wonkette that I found quite pleasing.

The more recent was in response to MSNBC's First Read describing the presidential press conference as too boring and policy-filled:

If all you can muster are condescending vagaries about the bad politics of the “average viewer” being treated like an adult, then don’t say anything. Because it’s bad for your country.

On the other hand, health care reform is a very difficult, tangly, economicky subject, and most people are too busy to read all the latest white papers on it. Which is why they elect representatives to go to the Capitol and make the right choices on their behalf!

UPDATE: AND ONE MORE HOT-POTATO OF A POINT. Obama should have been more wonky! People need to understand how crucial good health care reform is to everything.

The earlier was regarding the treatment of congressional interns who answer the phone of constituents across the country, many of whom believe ridiculous things like "the government will invade your house and force you to accept public health care."

So, today or maybe even tomorrow, call your representatives — your senators, your congresscritter, maybe a couple of Republicans in the House, why not? — and politely express your support for whatever libtard Nobama stuff you like.

You could say something along these lines:

“Oh hi, what is up, I know you people are just getting so many calls from angry old white people. Just wanted to politely register my support for the Obama health care or whatever’s the big deal right now. And I promise not to march on Washington and just make the Metro unbearable. Thanks for interning, we appreciate your free work!”

Here, find your reps’ phone numbers, just enter your zip code, easy!

Saturday, July 4, 2009

Happy Independence Day

Thus an omnibus, poorly-thought-out post.

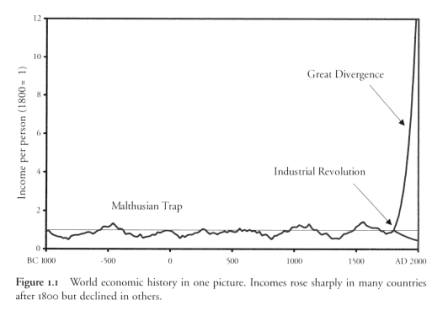

Paul Krugman posted a few times on the subject of Malthus, and how his theory has largely been rejected because the two centuries that followed his theory were the only ones on record (out of 60(!) i.e., going back to 4000 B.C.E. or so) in which income gains weren't eaten up by the increase in population. Many attribute this to the magic of capitalism or the magic of the industrial revolution; I, however, would like to hypothesize (based on very little data... scientific method in process!) that this economic boom we call the modern era could have been merely the result the "western world" (which is usually what our extended economic data is based on) discovering another continent to move into, thus easing the pressures of increased population. This would mean that this boom that we attribute to capitalism or industrialism is only temporary, now that we are living in a global economy.

Krugman also points out that the risk of deflation was and is very real, thus providing some additional justification for deficit stimulus spending in the face of those who would suggest it could cause inflation.

Ed Glaeser, however, points out some of the disappointments in the stimulus spending on transportation, specifically what a disproportionate amount has gone to fund roads in places that already have plenty of existing roads in comparison to people. Though his point is valid that "mass transit" is typically helpful only where "mass population" already exists, I might like to believe that implementing an actually-useful mass transit system will encourage people to live more densely. At the very least, if that alone does not induce more dense living significantly, I'd prefer we treat the greater efficiency of denser living as a goal and not a mere circumstance with which to reckon.

My own colleague (I use that term charitably*) Mano Singham posted yesterday on the subject of the pursuit of happiness, drawing heavily from Vonnegut. I have never formally read any Vonnegut, but every excerpt I come across, every time I hear him speak, I am intrigued and feel as though I've found a kindred spirit. I'd like to remind everyone, however, that Jefferson's inalienable rights were borrowed and subsequently reinterpreted from John Locke, who instead wrote these rights to be "Life, Health, Liberty, and Property." Though it may be more noble to pursue happiness than property (though again, it is worth noting Vonnegut's question of whether happiness can be pursued), I am suspicious of the swapping of one for the other.

The Mark Sanford movie trailer embedded at the end is also semi-comical, if for only the final line of "Maybe like, five celebrities will die at once and everybody will just forget about it."

Sarah Palin resigned, ha ha, and there are any number of poorly-thought-out (like this post!) reasons why this might have happened. My favorites are the ones given by your wonkette, “I’m going to resign because governing a state is hard when you have absolutely no interest in governing a state,” and that given by my dad, which is that she got offered a position commenting for fox news that was to good to pass up.

This was far more comical last night when I read it than it appears to me now; I thus pass along with no further comment except to point out that per commenter gumplr, the final Lincoln statue does in fact look like Egon Spengler.

Postscript:

I note that on the holiday celebrating our nation's independence my mind naturally is drawn to the elusivity of pursuing happiness as our founding father suggested and the potential hazards of relying on the effects of this continent's discovery for our well-being. The irony is not lost. Ahhh, holidays.

* - Lest anyone be confused, the charity here is toward myself, or perhaps the nature of the relationship. We are employed by the same school, myself in a far less prestigious position.

Paul Krugman posted a few times on the subject of Malthus, and how his theory has largely been rejected because the two centuries that followed his theory were the only ones on record (out of 60(!) i.e., going back to 4000 B.C.E. or so) in which income gains weren't eaten up by the increase in population. Many attribute this to the magic of capitalism or the magic of the industrial revolution; I, however, would like to hypothesize (based on very little data... scientific method in process!) that this economic boom we call the modern era could have been merely the result the "western world" (which is usually what our extended economic data is based on) discovering another continent to move into, thus easing the pressures of increased population. This would mean that this boom that we attribute to capitalism or industrialism is only temporary, now that we are living in a global economy.

Krugman also points out that the risk of deflation was and is very real, thus providing some additional justification for deficit stimulus spending in the face of those who would suggest it could cause inflation.

Ed Glaeser, however, points out some of the disappointments in the stimulus spending on transportation, specifically what a disproportionate amount has gone to fund roads in places that already have plenty of existing roads in comparison to people. Though his point is valid that "mass transit" is typically helpful only where "mass population" already exists, I might like to believe that implementing an actually-useful mass transit system will encourage people to live more densely. At the very least, if that alone does not induce more dense living significantly, I'd prefer we treat the greater efficiency of denser living as a goal and not a mere circumstance with which to reckon.

My own colleague (I use that term charitably*) Mano Singham posted yesterday on the subject of the pursuit of happiness, drawing heavily from Vonnegut. I have never formally read any Vonnegut, but every excerpt I come across, every time I hear him speak, I am intrigued and feel as though I've found a kindred spirit. I'd like to remind everyone, however, that Jefferson's inalienable rights were borrowed and subsequently reinterpreted from John Locke, who instead wrote these rights to be "Life, Health, Liberty, and Property." Though it may be more noble to pursue happiness than property (though again, it is worth noting Vonnegut's question of whether happiness can be pursued), I am suspicious of the swapping of one for the other.

The Mark Sanford movie trailer embedded at the end is also semi-comical, if for only the final line of "Maybe like, five celebrities will die at once and everybody will just forget about it."

Sarah Palin resigned, ha ha, and there are any number of poorly-thought-out (like this post!) reasons why this might have happened. My favorites are the ones given by your wonkette, “I’m going to resign because governing a state is hard when you have absolutely no interest in governing a state,” and that given by my dad, which is that she got offered a position commenting for fox news that was to good to pass up.

This was far more comical last night when I read it than it appears to me now; I thus pass along with no further comment except to point out that per commenter gumplr, the final Lincoln statue does in fact look like Egon Spengler.

Postscript:

I note that on the holiday celebrating our nation's independence my mind naturally is drawn to the elusivity of pursuing happiness as our founding father suggested and the potential hazards of relying on the effects of this continent's discovery for our well-being. The irony is not lost. Ahhh, holidays.

* - Lest anyone be confused, the charity here is toward myself, or perhaps the nature of the relationship. We are employed by the same school, myself in a far less prestigious position.

Monday, June 29, 2009

Nate Silver does a quick tally of what countries' GDP could add up to the 5% of total GDP predicted to be lost to global warming. He manages to get 81 countries, 43% of the world's population, into a group that could, hypothetically, be the five percent of GDP lost. He writes:

I'm not exactly sure what mechanism Jim Manzi had in mind for the mechanism of GDP decline, but I'm not exactly sure I also don't suspect that I'd find the tropics to be most effected in terms of GDP. In terms of total damage, or lives lost, perhaps.

Given that the solution to global warming in general is increased sustainability (broadly speaking, of course), and that energy sustainability will have not only the environmental effects but the infrastructure effects, failure to implement such sustainability measures will have an even greater effect on GDP on those places where fossil fuel energy is used most, in the most industrialized nations, not the bottom-rung-of-GDP nations that Nate selected. But, then again, maybe Manzi ignored these effects entirely.

Coincidentally, or not, a lot of these countries are located in the tropics, where global warming would probably have its most pernicious effects. True, they would probably not be entirely eradicated even under some of the worst-case, fattest-tail climate change assumptions.

I'm not exactly sure what mechanism Jim Manzi had in mind for the mechanism of GDP decline, but I'm not exactly sure I also don't suspect that I'd find the tropics to be most effected in terms of GDP. In terms of total damage, or lives lost, perhaps.

Given that the solution to global warming in general is increased sustainability (broadly speaking, of course), and that energy sustainability will have not only the environmental effects but the infrastructure effects, failure to implement such sustainability measures will have an even greater effect on GDP on those places where fossil fuel energy is used most, in the most industrialized nations, not the bottom-rung-of-GDP nations that Nate selected. But, then again, maybe Manzi ignored these effects entirely.

Krugman's Comment

on the subject of Mankiw's article:

Update: Mankiw responds to Paul.

This is moreso a testament to Greg's civility in these issues. Paul Krugman is, however, justifiably bitter after being called all kinds of nasty things through the previous administration's tenure. Hence, however, my choice to highlight the meat of Paul's response rather than the insults.

the standard competitive market model just doesn’t work for health care: adverse selection and moral hazard are so central to the enterprise that nobody, nobody expects free-market principles to be enough.

Update: Mankiw responds to Paul.

This is moreso a testament to Greg's civility in these issues. Paul Krugman is, however, justifiably bitter after being called all kinds of nasty things through the previous administration's tenure. Hence, however, my choice to highlight the meat of Paul's response rather than the insults.

Saturday, June 27, 2009

Mankiw's Sunday Article on the Public Option

It's probably clear that I give Greg Mankiw a decent amount of respect as a conservative economist. Usually his positions are stated by revealing the observed mathematical relationships and then explaining why he would value a particular outcome, less than letting a bias guide his interpretation of the numbers.

Thus, I'm actually kind of suprised how unimpressed I am with his Sunday article on the public option, and also surprised with to how much I've already responded.

A few comments, for example:

That's about all that's new in there, as near as I can tell.

Unrelatedly, it's worth reading Dan Froomkin's last article with the Washington Post, summarizing his 5-year career as a columnist.

Thus, I'm actually kind of suprised how unimpressed I am with his Sunday article on the public option, and also surprised with to how much I've already responded.

A few comments, for example:

True, Medicare’s administrative costs are low, but it is easy to keep those costs contained when a system merely writes checks without expending the resources to control wasteful medical spending."Expending the resources to control wasteful spending" is a positive way to restate the stories we've all heard of insurance companies dropping coverage on a patient once the patient finally needs it for say, an injury or a cancer diagnosis.

Similarly, a monopsony — a buyer without competitors — can reduce the price it pays below the competitive level by reducing the quantity it demands. This lesson applies directly to the market for health care. If the government has a dominant role in buying the services of doctors and other health care providers, it can force prices down.It is my hope that a publicly run insurance option would intend to cover everyone (say, through a mandate with subsidies) and that the whole point of having this option is such that it doesn't have a say in how much it demands, and it's demand would merely represent the demand of all the people covered under it.

It is no wonder that the American Medical Association opposes the public option.Most recently I've heard that the AMA counts about 30% of doctors among its numbers.

That's about all that's new in there, as near as I can tell.

Unrelatedly, it's worth reading Dan Froomkin's last article with the Washington Post, summarizing his 5-year career as a columnist.

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Keeping Costs Down (And Going Out On A Few Limbs)

The President says of a public option:

And Nate Silver agrees. Robert Reich has his own explanation of why that's bunk.

It strikes me as silly circular argument. Michael Steele says that if the problem is prices, lets just "do the deal" and cut prices. Then George Will says that you can't have competition from a public insurer, because insurance companies will be forced to cut profits and lower prices!

Incidentally, in Nate Silver's post, as well as Greg Mankiw's, a lot of other ideas for keeping health care costs down are discussed. For example, does subsidizing health insurance (sort of a back door subsidy through making it income-tax-free (see Nate's)) benefit the wallet of the consumer/patient or the insurance company? Given that the market for health care is one with low elasticity of demand (people perceive it as a necessity, required whatever the cost), it may be mostly to the benefit of the insurance company. Or as David Brooks comments:

Professor Mankiw writes about the disparity between American doctors' income and those of other countries with universal health coverage. The typical argument that tends to follow here might be that the doctors in the US are far more talented, and if we were to do something that could effect their incomes, we might not be able to attract such talented doctors.

I'm not quite sure I can sympathize with this sentiment. Does this higher income indicate a greater degree of talent or education? Typically, licensure in the US requires education at a medical establishment in the US, and though the US educational establishment is well-sought internationally, it is likely to be because of the income one is able to earn with a practice in the US. International comparisons on tests of hard knowledge have been of late tending to favor the products of a European education.

So what else could produce such a higher income? As Mankiw discusses, education of doctors in the U.S. is usually something that is built into the price of an insurance premium, because a Doctor will usually take a loan to fund medical school and repay it while in practice (thus, this educational cost is actually education + interest), while in some European nations, medical education might be publicly funded (still coming from the same people, taxpayer/patients, but in this case under a different heading). This will make reported incomes higher in the U.S. while a lot of that price is actually repaying for education.

Another easy explanation: too few doctors. This is something that is regulated by the admission departments of American centers of medical education. These organizations have the incentive to appease the AMA to stay accredited, which has the incentive to keep class sizes small to keep their incomes up. Part of a solution could be to offer schools an incentive to increase their class sizes (aside from merely the additional tuition).

The issue Mankiw brings up regarding doctor training is an important distinction to consider in discussing healthcare costs, but it could also provide a solution. The difference here is timing (which may not be an issue: the government will also have to pay interest if they need to go into debt to fund any of these proposals) and incentives. A person considering medical school might be more swayed by the idea of a free education followed by a lower income later. At least I would be.

Why would it drive private insurance out of business? If private insurers say that the marketplace provides the best quality health care; if they tell us that they’re offering a good deal, then why is it that the government, which they say can’t run anything, suddenly is going to drive them out of business? That’s not logical.

And Nate Silver agrees. Robert Reich has his own explanation of why that's bunk.

It strikes me as silly circular argument. Michael Steele says that if the problem is prices, lets just "do the deal" and cut prices. Then George Will says that you can't have competition from a public insurer, because insurance companies will be forced to cut profits and lower prices!

Incidentally, in Nate Silver's post, as well as Greg Mankiw's, a lot of other ideas for keeping health care costs down are discussed. For example, does subsidizing health insurance (sort of a back door subsidy through making it income-tax-free (see Nate's)) benefit the wallet of the consumer/patient or the insurance company? Given that the market for health care is one with low elasticity of demand (people perceive it as a necessity, required whatever the cost), it may be mostly to the benefit of the insurance company. Or as David Brooks comments:

The exemption is a giant subsidy to the affluent. It drives up health care costs by encouraging luxurious plans and by separating people from the consequences of their decisions. Furthermore, repealing the exemption could raise hundreds of billions of dollars, which could be used to expand coverage to the uninsured.

Professor Mankiw writes about the disparity between American doctors' income and those of other countries with universal health coverage. The typical argument that tends to follow here might be that the doctors in the US are far more talented, and if we were to do something that could effect their incomes, we might not be able to attract such talented doctors.

I'm not quite sure I can sympathize with this sentiment. Does this higher income indicate a greater degree of talent or education? Typically, licensure in the US requires education at a medical establishment in the US, and though the US educational establishment is well-sought internationally, it is likely to be because of the income one is able to earn with a practice in the US. International comparisons on tests of hard knowledge have been of late tending to favor the products of a European education.

So what else could produce such a higher income? As Mankiw discusses, education of doctors in the U.S. is usually something that is built into the price of an insurance premium, because a Doctor will usually take a loan to fund medical school and repay it while in practice (thus, this educational cost is actually education + interest), while in some European nations, medical education might be publicly funded (still coming from the same people, taxpayer/patients, but in this case under a different heading). This will make reported incomes higher in the U.S. while a lot of that price is actually repaying for education.

Another easy explanation: too few doctors. This is something that is regulated by the admission departments of American centers of medical education. These organizations have the incentive to appease the AMA to stay accredited, which has the incentive to keep class sizes small to keep their incomes up. Part of a solution could be to offer schools an incentive to increase their class sizes (aside from merely the additional tuition).

The issue Mankiw brings up regarding doctor training is an important distinction to consider in discussing healthcare costs, but it could also provide a solution. The difference here is timing (which may not be an issue: the government will also have to pay interest if they need to go into debt to fund any of these proposals) and incentives. A person considering medical school might be more swayed by the idea of a free education followed by a lower income later. At least I would be.

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Michael Steele Incomprehensively Discusses Health Care.

What the hell. At least there are some people (even on both sides of the aisle!) who are actually suggesting ideas, imperfect or impractical.

As opposed to any systemic change in the health care system, Michael Steele suggests:

If he is including "systemic and pervasive reasons that for-profit insurance companies would work to deny access to its policyholders" among the "host of reasons which may be legitimate," then a systemic reform of the medical insurance industry is an entirely appropriate response.

Never mind that. Let's just do the deal, whatever that means.

As opposed to any systemic change in the health care system, Michael Steele suggests:

If I don't have access because of... a host of reasons which may be legitimate, then address that.

If he is including "systemic and pervasive reasons that for-profit insurance companies would work to deny access to its policyholders" among the "host of reasons which may be legitimate," then a systemic reform of the medical insurance industry is an entirely appropriate response.

Never mind that. Let's just do the deal, whatever that means.

Monday, June 22, 2009

A Little Bit on H.R. 2454 (Waxman's Cap'N'Trade)

I get a little disconcerted when "prevention" in health care is discussed in terms of more medication rather than lifestyle and environmental changes.

Incidentally, today is the 40-year anniversary of my hometown's flammable water catastrophe (which, in addition to becoming "a galvanizing symbol for the environmental movement," inspired a pretty okay beverage as well).

Likewise, I get a little disconcerted when environmental change is discussed as an overall cost to society as Paul Krugman does here. Granted, his point is that the overall cost is very low (18 cents a day), according to the CBO report:

Emphasis mine. This bill is apparently 17% environmental solution and 83% corporate welfare.

The CBO's report states that "reducing emissions to the level required by the cap would be accomplished mainly by stemming demand for carbon-based energy by increasing its price." The effect is going to be drastically reduced if the price is raised only for 17% of polluters.

So why am I arguing that we should raise the price of polluting when I began with the idea that we shouldn't focus on the cost? Because the money raised through auctioning allowances doesn't just disappear when it enters the federal treasury (technically speaking, of course. We can certainly come up with a lot of, say, symbolic reasons to argue that the money has disappeared). The money can offset existing income taxes (to the benefit of those in lower incomes who might have undue strain placed unto them with higher energy costs – though maintaining a better set of incentives to conserve energy) or fund something like health care to take care of those who accidentally fell in the cuyahoga river back before we charged polluters.

Jefferey J. Smith relates the two:

His ending conclusion is more optimistic than I might suggest, but the point remains that the benefits aren't discussed nearly as much as the costs.

Also from the CBO study, on the subject of undiscussed benefits:

Incidentally, today is the 40-year anniversary of my hometown's flammable water catastrophe (which, in addition to becoming "a galvanizing symbol for the environmental movement," inspired a pretty okay beverage as well).

Likewise, I get a little disconcerted when environmental change is discussed as an overall cost to society as Paul Krugman does here. Granted, his point is that the overall cost is very low (18 cents a day), according to the CBO report:

CBO estimates that the price of an allowance, which would permit one ton of GHG emissions measured in CO2 equivalents, in 2020 would be $28. H.R. 2454 would require the federal government to sell a portion of the allowances and distribute the remainder to specified entities at no cost. The portions of allowances that were sold and distributed for free would vary from year to year. This analysis focuses on the year 2020, when 17 percent of the allowances would be sold by the government and the remaining 83 percent would be given away.

Emphasis mine. This bill is apparently 17% environmental solution and 83% corporate welfare.

The CBO's report states that "reducing emissions to the level required by the cap would be accomplished mainly by stemming demand for carbon-based energy by increasing its price." The effect is going to be drastically reduced if the price is raised only for 17% of polluters.

So why am I arguing that we should raise the price of polluting when I began with the idea that we shouldn't focus on the cost? Because the money raised through auctioning allowances doesn't just disappear when it enters the federal treasury (technically speaking, of course. We can certainly come up with a lot of, say, symbolic reasons to argue that the money has disappeared). The money can offset existing income taxes (to the benefit of those in lower incomes who might have undue strain placed unto them with higher energy costs – though maintaining a better set of incentives to conserve energy) or fund something like health care to take care of those who accidentally fell in the cuyahoga river back before we charged polluters.

Jefferey J. Smith relates the two:

To bring down costs even more, let’s clean up the environment, which would stop stressing out our immune systems, and let’s expand leisure for everyone, which would stop stressing out us. We can reach both goals via geonomics. That is, when we require members of society to pay land dues, they tend to use land efficiently and not pollute. And when we endow members of society with shares of recovered “rents”, then we all can afford to work less. With geonomics in place, we might not need any socialized medical attention at all.

His ending conclusion is more optimistic than I might suggest, but the point remains that the benefits aren't discussed nearly as much as the costs.

Also from the CBO study, on the subject of undiscussed benefits:

This analysis does not address other provisions of the bill, nor does it encompass the potential benefits associated with any changes in the climate that would be avoided as a result of the legislation...

For the remaining portion of the net cost, households in the lowest income quintile would see an average net benefit of about $40 in 2020.

Friday, June 19, 2009

Health Care v. Health Insurance.

Gary Becker writes recently about arguments used to disparage the U.S. health care system:

His point is certainly valid, but why should the U.S. faring more poorly on life style indicators be ignored? Is this something that is completely inaccessible by health care policy?

As the nearly clichéd argument goes, if health care is a for-profit business as it is in the United States, health care providers have an incentive not to keep people healthy, but to allow them to be sick and then treat them.

Put another way: Pfizer has just as much an interest in keeping agricultural subsidies as does a company like Cargill, and just because it's managed by a different department in the federal government doesn't mean it's unrelated to the United States' deficient health. If the connection is unclear, the particular hypothetical I'm picturing is one in which, say, the "burden"* of the corn subsidy goes directly to a conglomerate like Cargill, while foods featuring corn by-products (i.e., it's infamous fructose-enfused syrup), which are now able to undercut more-whole foods, give consumers the incentive to eat themselves into obesity and treat themselves with Pfizer-produced pharmaceuticals.

Elimination of a corn subsidy (to continue with such an example) would not only appease deficit hawks, but also correct incentives in the grocery store to encourage a healthier population. And in addition to perfectly conservative reasons why we might want a public option for health care, perhaps even a tax on overly-produced-and-thus-kind-of-fake foods might be in order to help the U.S. with it's "life style indicators."

This tax could even be a carbon tax; though there are certainly exceptions, the more energy that goes into producing your food, the greater it's association tends be with chronic diseases later in life. The system of fossil fuel to make fertilizer to grow corn to feed cows to raise and produce red meat could possibly be the least efficient energy-to-food calorie ratio available in a grocery store, for example.

--

* Just as the elasticities effect who gets the burden of a tax applied to that market, so would the same effect who gets the benefit of a subsidy, though this is discussed less often.

--

Update:

I didn't realize Becker's post would stir up as much blogger-ire as it did, but Paul Krugman and Andrew Gelman of 538 both have retorts to Becker's point (as also quoted by Greg Mankiw).

Instead, the American system has sometimes been found wanting simply because life expectancies in the United States are at best no better than those in France, Sweden, Japan, Germany, and other countries that spend considerably less on health care, both absolutely and relative to their GDPs.

...Although such calculations show that improvements in life expectancy are worth a lot to most people, national differences in life expectancies are a highly imperfect indicator of the effectiveness of health delivery systems. For example, life styles are important contributors to health, and the US fares poorly on many life style indicators, such as incidence of overweight and obese men, women, and teenagers. To get around such problems, some analysts compare not life expectancies but survival rates from different diseases. The US health system tends to look pretty good on these comparisons.

His point is certainly valid, but why should the U.S. faring more poorly on life style indicators be ignored? Is this something that is completely inaccessible by health care policy?

As the nearly clichéd argument goes, if health care is a for-profit business as it is in the United States, health care providers have an incentive not to keep people healthy, but to allow them to be sick and then treat them.

Put another way: Pfizer has just as much an interest in keeping agricultural subsidies as does a company like Cargill, and just because it's managed by a different department in the federal government doesn't mean it's unrelated to the United States' deficient health. If the connection is unclear, the particular hypothetical I'm picturing is one in which, say, the "burden"* of the corn subsidy goes directly to a conglomerate like Cargill, while foods featuring corn by-products (i.e., it's infamous fructose-enfused syrup), which are now able to undercut more-whole foods, give consumers the incentive to eat themselves into obesity and treat themselves with Pfizer-produced pharmaceuticals.

Elimination of a corn subsidy (to continue with such an example) would not only appease deficit hawks, but also correct incentives in the grocery store to encourage a healthier population. And in addition to perfectly conservative reasons why we might want a public option for health care, perhaps even a tax on overly-produced-and-thus-kind-of-fake foods might be in order to help the U.S. with it's "life style indicators."

This tax could even be a carbon tax; though there are certainly exceptions, the more energy that goes into producing your food, the greater it's association tends be with chronic diseases later in life. The system of fossil fuel to make fertilizer to grow corn to feed cows to raise and produce red meat could possibly be the least efficient energy-to-food calorie ratio available in a grocery store, for example.

--

* Just as the elasticities effect who gets the burden of a tax applied to that market, so would the same effect who gets the benefit of a subsidy, though this is discussed less often.

--

Update:

I didn't realize Becker's post would stir up as much blogger-ire as it did, but Paul Krugman and Andrew Gelman of 538 both have retorts to Becker's point (as also quoted by Greg Mankiw).

Thursday, January 15, 2009

The Permanent Grassroots Campaign.

I don't believe Michael Scherer reads the Pigouist, but it'd be nice to think it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)